- Home

- Medical news & Guidelines

- Anesthesiology

- Cardiology and CTVS

- Critical Care

- Dentistry

- Dermatology

- Diabetes and Endocrinology

- ENT

- Gastroenterology

- Medicine

- Nephrology

- Neurology

- Obstretics-Gynaecology

- Oncology

- Ophthalmology

- Orthopaedics

- Pediatrics-Neonatology

- Psychiatry

- Pulmonology

- Radiology

- Surgery

- Urology

- Laboratory Medicine

- Diet

- Nursing

- Paramedical

- Physiotherapy

- Health news

- Fact Check

- Bone Health Fact Check

- Brain Health Fact Check

- Cancer Related Fact Check

- Child Care Fact Check

- Dental and oral health fact check

- Diabetes and metabolic health fact check

- Diet and Nutrition Fact Check

- Eye and ENT Care Fact Check

- Fitness fact check

- Gut health fact check

- Heart health fact check

- Kidney health fact check

- Medical education fact check

- Men's health fact check

- Respiratory fact check

- Skin and hair care fact check

- Vaccine and Immunization fact check

- Women's health fact check

- AYUSH

- State News

- Andaman and Nicobar Islands

- Andhra Pradesh

- Arunachal Pradesh

- Assam

- Bihar

- Chandigarh

- Chattisgarh

- Dadra and Nagar Haveli

- Daman and Diu

- Delhi

- Goa

- Gujarat

- Haryana

- Himachal Pradesh

- Jammu & Kashmir

- Jharkhand

- Karnataka

- Kerala

- Ladakh

- Lakshadweep

- Madhya Pradesh

- Maharashtra

- Manipur

- Meghalaya

- Mizoram

- Nagaland

- Odisha

- Puducherry

- Punjab

- Rajasthan

- Sikkim

- Tamil Nadu

- Telangana

- Tripura

- Uttar Pradesh

- Uttrakhand

- West Bengal

- Medical Education

- Industry

Therapeutic hypothermia may significantly increase death after neonatal encephalopathy: Lancet

The results showed that 50 percent of the infants in the group who received the cooling treatment died or had moderate or severe disability.

London, UK: Therapeutic hypothermia may significantly increase the risk of death and does not reduce the combined outcome of death or disability at 18 months after neonatal encephalopathy, show results from a recent study led by Imperial College London. Therapeutic hypothermia is a procedure used widely for the treatment of birth-related brain damage in newborn babies in low and middle-income countries (LMICs).

The study findings are published in the journal The Lancet Global Health.

The findings suggest that the treatment should not be offered as a treatment for neonatal encephalopathy in LMICs even when tertiary neonatal intensive care facilities are available.

The study, of 408 babies with suspected birth-related brain damage across India, Sri Lanka, and Bangladesh, used a technique called therapeutic hypothermia. This technique cools a baby's body temperature by four degrees, by placing them on a type of cooling mat.

Previous evidence suggests the cold temperatures may help reduce brain cell damage and cell death.

The cooling treatment is widely used around the world, and evidence from multiple trials in high-income nations suggests the treatment reduces death and disability in babies.

However, although the treatment is also used extensively in LMICs, until now there have been few trials analyzing the effectiveness of the treatment in LMICs.

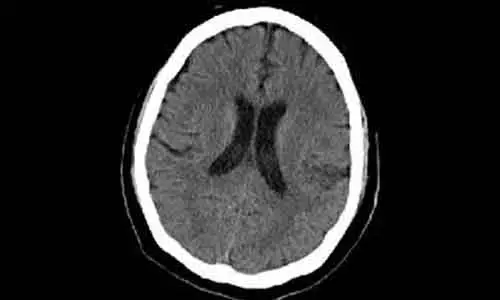

All babies in the new study were suspected to have suffered brain damage during birth, and suffer from a condition called neonatal encephalopathy. This condition means a baby has abnormal brain function, and is normally caused by a lack of oxygen.

Neonatal encephalopathy is the cause of one million deaths worldwide every year, of which 99 percent occur in LMICs.

In the new trial, funded by the Garfield Weston Foundation, 206 babies with suspected brain damage received the cooling therapy after birth, while 202 babies received no treatment after birth.

The study, called the HELIX trial, was a randomized controlled trial. After the families of the babies had agreed for them to take part in the trial, the babies were randomly allocated to receive the cooling therapy, as widely used in many parts of the world, or to not receive the cooling therapy.

Babies in both groups received comprehensive treatment in intensive care units. The cooling treatment was initiated within six hours of birth, and continued for 72 hours, while the babies were closely monitored.

Advanced MRI scan was used to assess their brain health at two weeks old, and the babies' general health at 18 months. Gauging the level of a child's development and disability is difficult before this age.

The results of the trial showed that 50 percent of the infants in the group who received the cooling treatment died or had moderate or severe disability.

In the control group, where the babies didn't receive the cooling treatment, 47 percent of infants died or had a moderate or severe disability.

The results also showed that 42 percent of children in the cooling treatment group died, while 31 percent of infants in the control group died.

All study sites were monitored closely by the Imperial College London team, who have extensive experience of therapeutic hypothermia, using real-time daily video conferencing to discuss the babies' health. The trial team also made site visits every three to four months and delivered training during the recruitment period.

The cooling treatment was administered using the same cooling device used in the UK, and the core body temperatures were closely within the target range of 33 - 34 degrees.

Professor Sudhin Thayyil, the lead author of the trial from Imperial's Department of Brain Sciences, said: "These data, from the HELIX trial, suggest therapeutic hypothermia, alongside high-quality intensive care treatment, does not reduce the risk of brain injury or death in LMICs. The findings also suggest the treatment may increase the risk of death, compared to babies who did not receive the treatment. Hence, hypothermia treatment should no longer be used as a treatment for neonatal encephalopathy in low and middle-income nations. International guidelines (ILCOR – International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation) on cooling therapy in LMIC should be immediately amended."

The study team says more research is now urgently needed to understand why the cooling treatment was ineffective and harmful.

The team suggests the babies in the trial, and more generally in LMICs, may have had a different type of brain injury than the type of brain injury seen in trials in high-income nations. Scans of the babies' brains suggested damage to connecting fibers in the brain rather than to deep brain structures. One suggestion is that the brain damage may have occurred at an early stage of the birth, or earlier in the pregnancy.

Reference:

The study titled, "Hypothermia for moderate or severe neonatal encephalopathy in low-income and middle-income countries (HELIX): a randomised controlled trial in India, Sri Lanka, and Bangladesh," is published in the journal The Lancet Global Health.

DOI: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/langlo/article/PIIS2214-109X(21)00264-3/fulltext

Hina Zahid Joined Medical Dialogue in 2017 with a passion to work as a Reporter. She coordinates with various national and international journals and association and covers all the stories related to Medical guidelines, Medical Journals, rare medical surgeries as well as all the updates in the medical field. Email: editorial@medicaldialogues.in. Contact no. 011-43720751

Dr Kamal Kant Kohli-MBBS, DTCD- a chest specialist with more than 30 years of practice and a flair for writing clinical articles, Dr Kamal Kant Kohli joined Medical Dialogues as a Chief Editor of Medical News. Besides writing articles, as an editor, he proofreads and verifies all the medical content published on Medical Dialogues including those coming from journals, studies,medical conferences,guidelines etc. Email: drkohli@medicaldialogues.in. Contact no. 011-43720751