- Home

- Medical news & Guidelines

- Anesthesiology

- Cardiology and CTVS

- Critical Care

- Dentistry

- Dermatology

- Diabetes and Endocrinology

- ENT

- Gastroenterology

- Medicine

- Nephrology

- Neurology

- Obstretics-Gynaecology

- Oncology

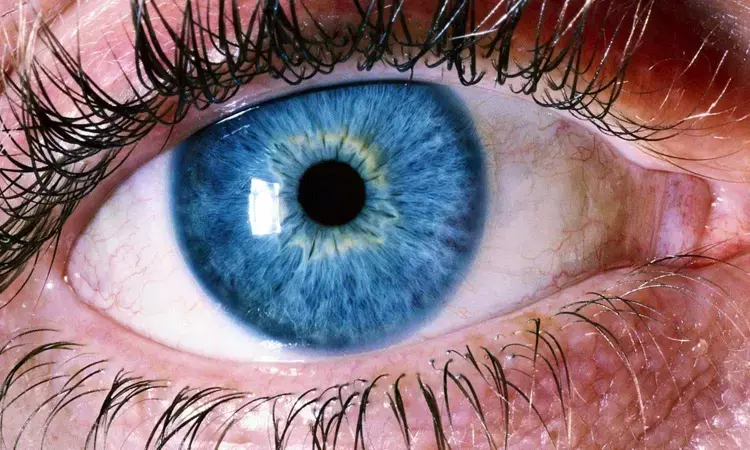

- Ophthalmology

- Orthopaedics

- Pediatrics-Neonatology

- Psychiatry

- Pulmonology

- Radiology

- Surgery

- Urology

- Laboratory Medicine

- Diet

- Nursing

- Paramedical

- Physiotherapy

- Health news

- Fact Check

- Bone Health Fact Check

- Brain Health Fact Check

- Cancer Related Fact Check

- Child Care Fact Check

- Dental and oral health fact check

- Diabetes and metabolic health fact check

- Diet and Nutrition Fact Check

- Eye and ENT Care Fact Check

- Fitness fact check

- Gut health fact check

- Heart health fact check

- Kidney health fact check

- Medical education fact check

- Men's health fact check

- Respiratory fact check

- Skin and hair care fact check

- Vaccine and Immunization fact check

- Women's health fact check

- AYUSH

- State News

- Andaman and Nicobar Islands

- Andhra Pradesh

- Arunachal Pradesh

- Assam

- Bihar

- Chandigarh

- Chattisgarh

- Dadra and Nagar Haveli

- Daman and Diu

- Delhi

- Goa

- Gujarat

- Haryana

- Himachal Pradesh

- Jammu & Kashmir

- Jharkhand

- Karnataka

- Kerala

- Ladakh

- Lakshadweep

- Madhya Pradesh

- Maharashtra

- Manipur

- Meghalaya

- Mizoram

- Nagaland

- Odisha

- Puducherry

- Punjab

- Rajasthan

- Sikkim

- Tamil Nadu

- Telangana

- Tripura

- Uttar Pradesh

- Uttrakhand

- West Bengal

- Medical Education

- Industry

Key Outcomes of the World Health Organization Package of Eye Care Interventions: JAMA

Globally, at least 1 billion people have vision impairment that could have been prevented or is yet to be addressed. This represents only a fraction of the total need for eyecare services; eye conditions are universal, and everyone, if they live long enough, will experience at least 1 eye condition requiring care. Vision impairment poses an enormous global financial burden.

Fortunately, there are effective public health strategies and clinical interventions that address the needs of persons with eye conditions and vision impairment; some are among the most cost-effective and feasible of all health care interventions to implement. Efforts to increase the coverage of these interventions during the past 30 years have yielded considerable dividends. The age adjusted prevalence of blindness due to avoidable causes has been decreasing, and there has been a substantial reduction in the number of children and adults who are blind due to vitamin A deficiency and infectious causes, such as onchocerciasis and trachoma.

Despite these successes, eye care services have been unable to keep pace with the increasing need associated with population, demographic, behavioral, and lifestyle trends that have led, and will continue to lead, to an increase in the number of non communicable eye conditions. To accentuate these challenges, significant inequalities in access to eye care services exist—the burden of eye conditions and vision impairment being greater in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) and underserviced populations. In many LMICs, essential ophthalmic equipment to manage eye conditions is frequently unavailable, particularly in the government sector, and eye care medicines and interventions are not integrated into the health insurance schemes. Thus, the costs associated with accessing eye care services pose a major barrier to addressing the inequities in access to, and provision of, these services across the population.

A handbook and resources to support the implementation of the PECI, targeting government health planners, have recently been published. These resources lack detail on the in-depth methods and results of the systematic review and expert consensus procedure that informed the development of the PECI. This information is valuable to (1) provide transparency on the development process and (2) highlight where gaps exist in the availability of high quality clinical practice guidelines in the field of eye care. This article by Stuart Keel and team describes the key outcomes of the development of the PECI.

A standardized stepwise approach that included the following stages:

(1) selection of priority eye conditions by an expert panel after reviewing epidemiological evidence and health facility data;

(2) identification of interventions and related evidence for the selected eye conditions from a systematic review of clinical practice guidelines (CPGs); stage 2 included a systematic literature search, screening of title and abstracts (excluding articles that were not relevant CPGs), full-text review to assess disclosure of conflicts of interest and affiliations, quality appraisal, and data extraction;

(3) expert review of the evidence extracted in stage 2, identification of missed interventions, and agreement on the inclusion of essential interventions suitable for implementation in low- and middle-income resource settings; and

(4) peer review.

Fifteen priority eye conditions were chosen. The literature search identified 3601 articles. Of these, 469 passed title and abstract screening, 151 passed full-text screening, 98 passed quality appraisal, and 87 were selected for data extraction. Little evidence (1 CPG identified) was available for pterygium, keratoconus, congenital eyelid disorders, vision rehabilitation, myopic macular degeneration, ptosis, entropion, and ectropion. In stage 3, domain-specific expert groups voted to include 135 interventions (57%) of a potential 235 interventions collated from stage 2. After synthesis across all interventions and eye conditions, 64 interventions (13 health promotion and education, 6 screening and prevention, 38 treatment, and 7 rehabilitation) were included in the PECI.

In this systematic review and expert consultation, authors described the key outcomes of the development of the PECI, which provides a set of recommended, evidence-based eye care interventions across the continuum of care, with the intention to facilitate planning for the delivery of eye care services in LMICs.

The systematic review of CPGs identified 98 high-quality guidelines, with 54 (55%) of these focused on only 4 eye conditions (conjunctivitis, diabetic retinopathy, glaucoma, and refractive error), whereas only 1 guideline or no guidelines were identified for 6 of the priority eye conditions (pterygium, keratoconus, myopic macular degeneration, vision rehabilitation, congenital disorders of the eyelid and lacrimal systems, ptosis, entropion, and ectropion), highlighting the need for high-quality clinical guidance on a wider range of eye conditions.

Of all interventions deliberated on by the expert Development Group, 73% were treatment focused with fewer identified for health promotion and education (6%), preventive and screening (17%), and rehabilitation (5%) interventions. Development Groups, made up of relevant clinical and academic experts, were essential in interpreting the collated evidence and ultimately determining that 43% of identified interventions were not adequately supported by evidence and/or were not feasible for implementation in LMICs.

In summary, the development of the PECI aims to facilitate the integration of eye care into national health services packages and policies by providing countries with information on evidence-based eye care interventions, including resource requirements for their implementation. This systematic review of CPGs highlighted a lack of high-quality CPGs published in English for some priority eye conditions. The results also suggest that promotion and education interventions, along with screening and prevention interventions, are underrepresented in current CPGs. These findings can assist in identifying gaps in high quality, English-language CPGs for eye conditions and further provide a useful reference for clinicians searching for high-quality CPGs to inform their clinical practice and offer a blueprint for eye care programs in low- and intermediate resource settings. Successful implementation of the PECI will require combined efforts from a range of stakeholders (ie, governments, WHO, nongovernment, private sector) to provide longterm investment and management, while also establishing closer linkages between eye care and relevant health programs and sectors.

Source: Stuart Keel, PhD; Gareth Lingham, PhD; Neha Misra; JAMA Ophthalmol.

doi:10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2022.4716

Dr Ishan Kataria has done his MBBS from Medical College Bijapur and MS in Ophthalmology from Dr Vasant Rao Pawar Medical College, Nasik. Post completing MD, he pursuid Anterior Segment Fellowship from Sankara Eye Hospital and worked as a competent phaco and anterior segment consultant surgeon in a trust hospital in Bathinda for 2 years.He is currently pursuing Fellowship in Vitreo-Retina at Dr Sohan Singh Eye hospital Amritsar and is actively involved in various research activities under the guidance of the faculty.

Dr Kamal Kant Kohli-MBBS, DTCD- a chest specialist with more than 30 years of practice and a flair for writing clinical articles, Dr Kamal Kant Kohli joined Medical Dialogues as a Chief Editor of Medical News. Besides writing articles, as an editor, he proofreads and verifies all the medical content published on Medical Dialogues including those coming from journals, studies,medical conferences,guidelines etc. Email: drkohli@medicaldialogues.in. Contact no. 011-43720751