- Home

- Medical news & Guidelines

- Anesthesiology

- Cardiology and CTVS

- Critical Care

- Dentistry

- Dermatology

- Diabetes and Endocrinology

- ENT

- Gastroenterology

- Medicine

- Nephrology

- Neurology

- Obstretics-Gynaecology

- Oncology

- Ophthalmology

- Orthopaedics

- Pediatrics-Neonatology

- Psychiatry

- Pulmonology

- Radiology

- Surgery

- Urology

- Laboratory Medicine

- Diet

- Nursing

- Paramedical

- Physiotherapy

- Health news

- Fact Check

- Bone Health Fact Check

- Brain Health Fact Check

- Cancer Related Fact Check

- Child Care Fact Check

- Dental and oral health fact check

- Diabetes and metabolic health fact check

- Diet and Nutrition Fact Check

- Eye and ENT Care Fact Check

- Fitness fact check

- Gut health fact check

- Heart health fact check

- Kidney health fact check

- Medical education fact check

- Men's health fact check

- Respiratory fact check

- Skin and hair care fact check

- Vaccine and Immunization fact check

- Women's health fact check

- AYUSH

- State News

- Andaman and Nicobar Islands

- Andhra Pradesh

- Arunachal Pradesh

- Assam

- Bihar

- Chandigarh

- Chattisgarh

- Dadra and Nagar Haveli

- Daman and Diu

- Delhi

- Goa

- Gujarat

- Haryana

- Himachal Pradesh

- Jammu & Kashmir

- Jharkhand

- Karnataka

- Kerala

- Ladakh

- Lakshadweep

- Madhya Pradesh

- Maharashtra

- Manipur

- Meghalaya

- Mizoram

- Nagaland

- Odisha

- Puducherry

- Punjab

- Rajasthan

- Sikkim

- Tamil Nadu

- Telangana

- Tripura

- Uttar Pradesh

- Uttrakhand

- West Bengal

- Medical Education

- Industry

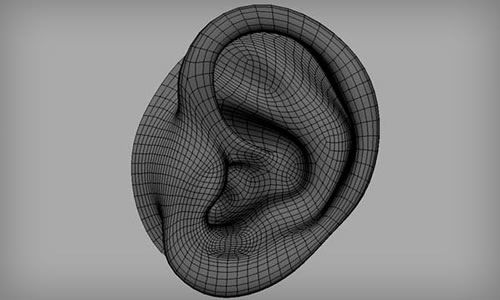

Researched identify new ears carving method using 3D printing

Researchers from the University of Washington (UW) have come forward with an evolved method to help trainee surgeons carve new ears from a paediatric rib cartilage like material by using 3D-printed moulds.

The new technique can help to treat children with a missing or under-developed ear, experienced surgeons harvest pieces of rib cartilage from the child and carve them into the framework of a new ear.

They take only as much of that precious cartilage as they need. That leaves medical residents without an authentic material to practice on. Some use pig or adult cadaver ribs, but children's ribs are of a different size and consistency.

The innovation could open the door for aspiring surgeons to become proficient in the sought-after but challenging procedure called auricular reconstruction.

"It's a huge advantage over what we are using today," said lead author Angelique Berens, a UW School of Medicine head and neck surgery resident.

As part of the study, three experienced surgeons practised carving, bending and suturing the UW team's silicone models, which were produced from a 3D-printed mould modelled from a CT scan of an 8-year-old patient.

They compared their firmness, feel and suturing quality to real rib cartilage, as well as a more expensive material made out of dental impression material.

All three surgeons preferred the UW models, and all recommended introducing them as a training tool for surgeons and surgeons-in-training.

"It's a surgery that more people could do but they are hesitant to start because they've never carved an ear before," said Kathleen Sie, a UW Medicine professor of head and neck surgery.

Another advantage is that because the UW models are printed from a CT scan, they mimic an individual's unique anatomy.

The findings were presented recently at the American Academy of Otolaryngology: Head and Neck Surgery conference in Dallas.

The new technique can help to treat children with a missing or under-developed ear, experienced surgeons harvest pieces of rib cartilage from the child and carve them into the framework of a new ear.

They take only as much of that precious cartilage as they need. That leaves medical residents without an authentic material to practice on. Some use pig or adult cadaver ribs, but children's ribs are of a different size and consistency.

The innovation could open the door for aspiring surgeons to become proficient in the sought-after but challenging procedure called auricular reconstruction.

"It's a huge advantage over what we are using today," said lead author Angelique Berens, a UW School of Medicine head and neck surgery resident.

As part of the study, three experienced surgeons practised carving, bending and suturing the UW team's silicone models, which were produced from a 3D-printed mould modelled from a CT scan of an 8-year-old patient.

They compared their firmness, feel and suturing quality to real rib cartilage, as well as a more expensive material made out of dental impression material.

All three surgeons preferred the UW models, and all recommended introducing them as a training tool for surgeons and surgeons-in-training.

"It's a surgery that more people could do but they are hesitant to start because they've never carved an ear before," said Kathleen Sie, a UW Medicine professor of head and neck surgery.

Another advantage is that because the UW models are printed from a CT scan, they mimic an individual's unique anatomy.

The findings were presented recently at the American Academy of Otolaryngology: Head and Neck Surgery conference in Dallas.

Meghna A Singhania is the founder and Editor-in-Chief at Medical Dialogues. An Economics graduate from Delhi University and a post graduate from London School of Economics and Political Science, her key research interest lies in health economics, and policy making in health and medical sector in the country. She is a member of the Association of Healthcare Journalists. She can be contacted at meghna@medicaldialogues.in. Contact no. 011-43720751

Next Story