- Home

- Medical news & Guidelines

- Anesthesiology

- Cardiology and CTVS

- Critical Care

- Dentistry

- Dermatology

- Diabetes and Endocrinology

- ENT

- Gastroenterology

- Medicine

- Nephrology

- Neurology

- Obstretics-Gynaecology

- Oncology

- Ophthalmology

- Orthopaedics

- Pediatrics-Neonatology

- Psychiatry

- Pulmonology

- Radiology

- Surgery

- Urology

- Laboratory Medicine

- Diet

- Nursing

- Paramedical

- Physiotherapy

- Health news

- Fact Check

- Bone Health Fact Check

- Brain Health Fact Check

- Cancer Related Fact Check

- Child Care Fact Check

- Dental and oral health fact check

- Diabetes and metabolic health fact check

- Diet and Nutrition Fact Check

- Eye and ENT Care Fact Check

- Fitness fact check

- Gut health fact check

- Heart health fact check

- Kidney health fact check

- Medical education fact check

- Men's health fact check

- Respiratory fact check

- Skin and hair care fact check

- Vaccine and Immunization fact check

- Women's health fact check

- AYUSH

- State News

- Andaman and Nicobar Islands

- Andhra Pradesh

- Arunachal Pradesh

- Assam

- Bihar

- Chandigarh

- Chattisgarh

- Dadra and Nagar Haveli

- Daman and Diu

- Delhi

- Goa

- Gujarat

- Haryana

- Himachal Pradesh

- Jammu & Kashmir

- Jharkhand

- Karnataka

- Kerala

- Ladakh

- Lakshadweep

- Madhya Pradesh

- Maharashtra

- Manipur

- Meghalaya

- Mizoram

- Nagaland

- Odisha

- Puducherry

- Punjab

- Rajasthan

- Sikkim

- Tamil Nadu

- Telangana

- Tripura

- Uttar Pradesh

- Uttrakhand

- West Bengal

- Medical Education

- Industry

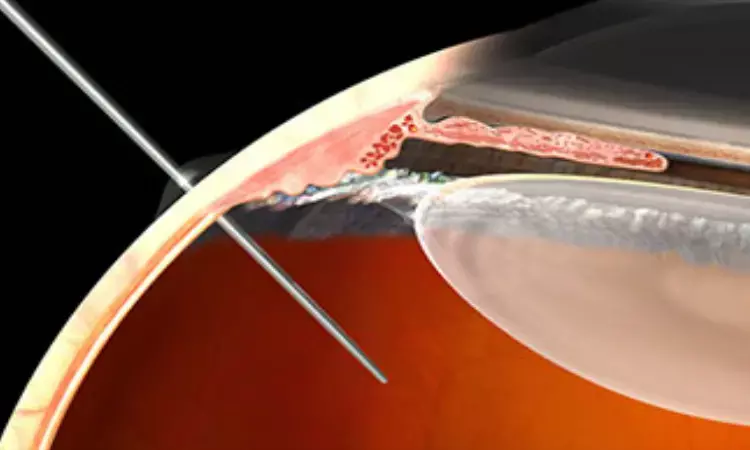

Evaluation of Series of Wrong Intravitreal Injection and importance to identify the factors associated: JAMA

Robin A. Vora and team described case series events associated with errors in intravitreal injections. Given the volume of injections performed worldwide, it is important to identify the factors associated with these wrong events to try to reduce their occurrences.

In this retrospective small case series of a convenience sample at KPNC between January 1, 2019, and December 30, 2020, cases of errors in intravitreal injection were identified either as part of a formal institutional quality review or by self-report of the involved surgeon during quality improvement discussions.

Case 1: Wrong Eye

A patient who was undergoing treatment for neovascular age related macular degeneration (nAMD) in both eyes with the same anti– vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) drug, but on different treatment intervals, presented for a repeated injection. The surgeon misread the last note and informed the staff to prepare the right eye for injection instead of the correct left eye. The patient had active consents for both eyes within the electronic record; thus, a new signed consent form was not requested. The patient did not object when the wrong eye was marked and prepped by the medical assistant. The surgeon then proceeded to inject the intended (but incorrect) eye. The error was realized after the surgeon reviewed the medical record, and the patient was notified. The patient was brought back a week later, and the correct eye was injected. It was noted afterwards that this team did not routinely use a surgical checklist or perform a pre-procedure timeout. Aside from an extra anti-VEGF injection, the patient experienced no harm.

Case 2: Wrong Eye

A patient with a history of branch retinal vein occlusion in the right eye presented for routine appointment. After examination, a decision was made to inject in the right eye. This was communicated to the patient and verbal consent was granted. A new signed consent form was not requested as an active electronic consent was on record. The right eye was marked and prepped by a medical assistant who also completed a pre-procedure checklist. The surgeon reentered the room but did not review the checklist or perform a surgical pause and went on to inject the unintended left eye. The patient was followed up closely by the physician, and no adverse event occurred in the erroneously injected eye. The patient returned several weeks later to have the correct eye injected.

Case 3: Wrong Medicine

A patient with age-related macular degeneration presented for routine follow-up. In the past, the patient had responded poorly following both repackaged ("compounded") bevacizumab (Avastin; Genentech) and ranibizumab (Lucentis; Genentech) but had responded well following aflibercept (EYLEA; Regeneron). Active consents for all 3 agents were present in the electronic medical record. On this visit, instead of the most recent record, the surgeon reviewed a past note where the patient received ranibizumab and ordered this medication again. It was prepared by the medical assistant and the surgeon injected the intended (but incorrect) agent into the correct eye. The surgeon noted the error while completing documentation and the patient was alerted. The retina team had not relied on a surgical checklist and it is unclear if a pre-procedure timeout was completed. The patient was brought back at a shorter interval, no harm was noted, and the correct treatment regimen was reinstituted.

Case 4: Wrong Medication Dose

A patient with clinically significant macular edema presented for an ordered injection of ranibizumab, 0.3mg, for which they had previously consented. The medical assistant, who was new to the retina service, erroneously pulled a box containing ranibizumab, 0.5 mg, from the refrigerator that stored all anti-VEGF medications. The assistant also failed to complete the pre-procedure checklist. The surgeon did not notice that the wrong concentration of the correct medicine had been placed on the injection tray. No timeout was performed. The surgeon proceeded to inject the wrong ranibizumab concentration into the correct eye. This error was noted as the surgeon completed their documentation and the patient was notified. The patient was brought back at a shorter interval, no harm was noted, and the correct treatment regimen was reinstituted.

Given the large volume of intravitreal injections performed by retinal specialists in office-based settings, it is unsurprising that cases of wrong intravitreal injections occur.

Nearly every step from the moment a patient enters the examination room to the actual procedure may be a potential source of error and result in a wrong injection. This is consistent with the "Swiss-cheese" model of system breakdown. For instance, upstream errors in writing or reviewing electronic medical record documentation can result in surgical confusions. Copy forward functions may lead to a wrong treatment if the surgeon fails to appropriately edit the new note and that mistake propagates downstream .Consents may also have substantial variability in wording. After consent, the process of site marking may be error prone. Finally, the common scenario of a surgeon leaving the examination room to attend to a different patient and then reentering later to perform the injection can be a source of subsequent error.

The potential for medication error within retina practice is also substantial. All anti-VEGF agents have comparable mechanisms of action and delivery methods. Medications are often stored in a single refrigerator where the wrong agent may be pulled. Indeed, the boxes for ranibizumab, 0.3 mg, and 0.5 mg, appear similar. Other factors such as supply constraints, insurance and cost issues, and patient preference may influence medication decisions, and such changes may be poorly communicated.

Data suggest that surgical timeouts and pre-procedure checklists are effective methods for reducing the risk of surgical confusions. To prevent future wrong intravitreal injections, we propose that retina surgeons standardize the injection pathway. First, there should be a set way of communicating the injection plan with staff, which clearly communicates agent and laterality. Patient consent and marking should be performed in a consistent manner. The team member preparing the patient should reconfirm the intended patient, eye, and medication while marking off a checklist to ensure all variables have been reconciled with the treatment plan. Finally, before injection, the surgeon should pause to perform a timeout.

Medical errors related to intravitreal injections have occurred with KPNC. As mistakes may be made anywhere along the injection pathway, it may be prudent to establish a systematic process around these procedures that ideally includes a checklist and surgical timeout in hopes of preventing these mistakes from propagating into the performance of a wrong intravitreous injection.

Source: Robin A. Vora, MD; Amar Patel, MD; Michael I. Seider, MD; Sam Yang, MD; JAMA Ophthalmol. doi:10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2021.3311

Dr Ishan Kataria has done his MBBS from Medical College Bijapur and MS in Ophthalmology from Dr Vasant Rao Pawar Medical College, Nasik. Post completing MD, he pursuid Anterior Segment Fellowship from Sankara Eye Hospital and worked as a competent phaco and anterior segment consultant surgeon in a trust hospital in Bathinda for 2 years.He is currently pursuing Fellowship in Vitreo-Retina at Dr Sohan Singh Eye hospital Amritsar and is actively involved in various research activities under the guidance of the faculty.

Dr Kamal Kant Kohli-MBBS, DTCD- a chest specialist with more than 30 years of practice and a flair for writing clinical articles, Dr Kamal Kant Kohli joined Medical Dialogues as a Chief Editor of Medical News. Besides writing articles, as an editor, he proofreads and verifies all the medical content published on Medical Dialogues including those coming from journals, studies,medical conferences,guidelines etc. Email: drkohli@medicaldialogues.in. Contact no. 011-43720751